The Death by Drowning of James Hoy from County Louth, Ireland on the Lehigh River at Glendon, Pennsylvania in the Aftermath of the Great Flood of 1862.

James Hoy's gravestone says that he was born in County Louth Ireland about 1792. The County Louth Genealogist in Dundalk, Ireland says the best match for him was born in 1794 just northeast of Louth Village in County Louth. Recent DNA matches support this.

His naturalization papers filed in Easton PA in 1860 state that his "Intended Place of Settlement" was Cooper's Furnace in Phillipsburg NJ, across the river from Easton PA. We know from the census of 1850 that he lived in Glendon PA, a tiny village south of Easton, and worked in the furnace there called the Glendon Iron Works.

Note that at this time, iron was produced from local supplies. The Durham Furnace and Ironworks, just south of Easton supplied the very large boats that George Washington used to cross the Delaware River and attack the Hessians at Trenton in 1776

His obituary (seen below) states that at the time of his death, he worked at the Lehigh Canal Lock in Glendon.

This lock began the stretch of canal which linked it to the Delaware Canal which runs along the Delaware River from Easton to Bristol just above Philadelphia. This lock was needed because the canal carrying coal from the southern fields of the Coal Region, ran along the other side of the river to Easton and the barges had to cross the Lehigh to re-enter the canal at the Glendon lock.

To achieve this, the engineers built a weir (small dam) across the river to control the flow of the water so that the barges could cross safely and enter the lock. The weir also supplied a steady flow of water into the last section of the canal.

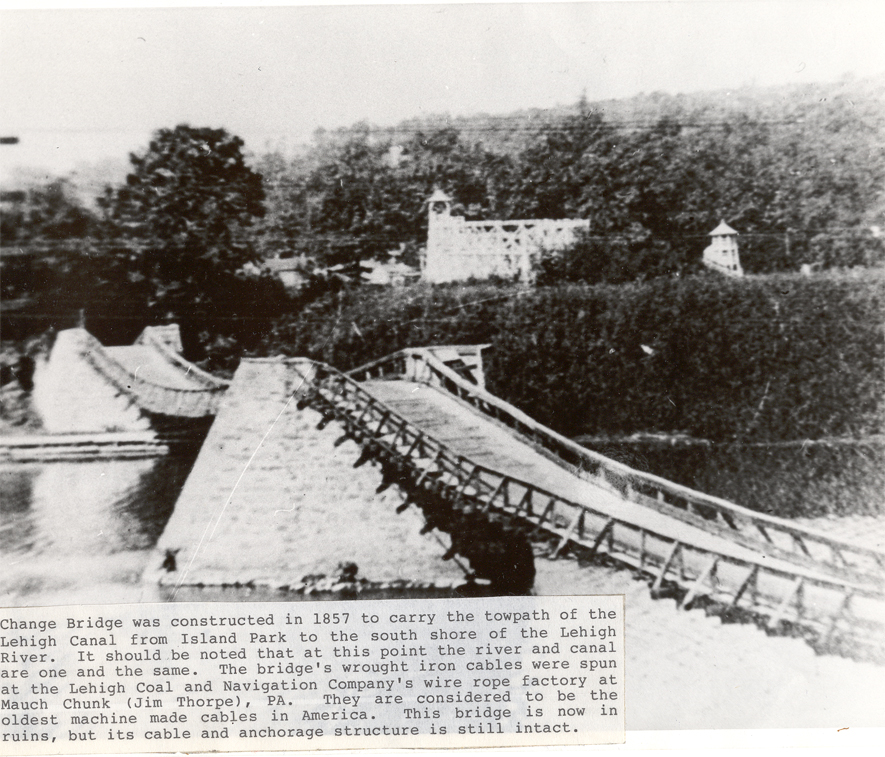

They also built a bridge across the river to allow the men and mules to cross the river and change sides. This was called a Change Bridge or sometimes a Chain bridge and Chain Dam. A small island was used to anchor some of the pylons and a popular Amusement Park was latter situated there.

The Google image below shows the weir is still there by the white water. At the bottom left is the tip of Island Park, but the Change Bridge is gone. At the bottom right we can see the remains of the Glendon Lock. Scroll down for older images of the lock area.

The daughters of James Hoy made the unusual decision to include the manner of their father's death on his gravestone and we know that he died while working on the canal. A month before his death, a great flood occurred on the Lehigh beginning in its headwaters in the mountains which killed several hundred people. Water and debris traveled down the river for some time. The canal lock at Glendon was necessary for the canal to function and damage to the weir or lock from debris would be a disaster. It is likely that James died while working to keep the floating debris from damaging the canal works.

The newspaper story shown below about the Lehigh Valley flood is from a Richmond Virginia paper during the second year of Civil War which indicates its importance.

Great flood in Pennsylvania.

Great flood in Pennsylvania.

A correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer furnishes the subjoined account of a disastrous flood in Lehigh Valley, Pa., which involved the loss of over one hundred lives and an immense amount of property:

A great storm has passed over Eastern Pennsylvania. In its wake are ruined fields of grain, stranded boats upon three great rivers, tottering and deserted houses, and at least one hundred dead bodies, dashed by a wild current against mountain rocks or floating logs. The works completed by the joint efforts of labor and capital, in a long course of years, have been swept almost out of existence in a single night. A score of iron furnaces have ceased to scatter their sparks into the air; hundreds of sturdy laborers have been thrown out of employment, and the scenes and incidents which marked the great flood of 1841 have been repeated upon an enlarged scale in June, 1862. In no section has the loss been as heavy as in the valley of the Lehigh, although the Schuylkill and Delaware vied with each other in their rage. The heavy rains of last week are fresh in the minds of our readers. On Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday last, the heavens were opened as if to inaugurate a new deluge. While the torrents swept the streets of the city and filled the sewers, they gradually accumulated in the mountain districts, changed rivulets into miniature rivers, and poured into the Lehigh, until its usually coal-black water assumed a muddy hue, and its bosom held the debris of the ruin which it had caused.

There is no river east of the Ohio that has rendered more service to man than the Lehigh. Almost at the point where it first emerges from the mountains, and assumes it name, it is checked, turned from its course and made a feeder to the canal.--The dams followed each other in succession until near Easton, a distance of over forty miles. They averaged at least one to every two miles. The head waters of the Lehigh were the first to feel the heavy rains, but no effect was visible until Wednesday night last. The extreme northern dam, it is believed, then gave way. This was at or near White Haven. The flood of water poured southward, carrying everything before it, and receiving new force and acquiring a new impetus as it over came each obstacle. Dam after dam was destroyed, until scarcely three remained between Mauch Chunk and White Haven.

The flood rolled on in the dead of night, heralding its progress by a terrible roar. It tore canal boats from their moorings, and swept them away like feathers, it dashed into the cellars, and mounted to the windows of residences upon its banks; it undermined the walls of towns, and now and then carried off a prize in the form of unlucky sleepers who could not escape. It encroached upon new territory, reaping the waving fields as no scythe could have done, and, in apparent revenge, seized fences and farm vehicles, and conveyed them to places unknown to man.

The storm spread along the river. The water actually rose fifteen feet in ten minutes. Fires were built at many points, and crowds collected around them, gazing into the black void beyond, and fearing to hear a human cry pierce the dull roar of the stream. More than one voice was thus raised for help. A canal boat drifted down, now inclining to one side, and dipping its deck into the river, and again reversing its position. On it were six men. Their shouts could be distinctly heard, but no aid could be afforded. The brief interval in which they passed the gazers was one of horror. The boat struck a rock at the head of an island near Bethlehem and split asunder. The man clung to the wreck, and finally managed, with one exception, to secure a resting place until the morning of Thursday. Before rescue came, they were joined by five others. These were taken to the shore by Mr. Yohe, of Bethlehem. The body of the drowned man was recovered and properly interred. It was terribly bruised.

There are many islands in the Lehigh. The soil is generally fertile, and they are nearly all well cultivated. This was the case with the one opposite Allentown. A covered bridge led to the main land. During the night a great crash aroused the three families living upon the island. Their only means of escape had been carried away by a bridge which formerly had spanned the stream above, and the two fabrics were now en route for the Delaware. --There was no boat, and even if there had been, the chances of safely rowing through such a swift current were but slight. How the families passed the night of Wednesday and the morning of Thursday we do not know. But when daylight appeared they found many acres of grain and garden transformed into a barren waste. The rich loam had given place to white sand, and fences and barnes had disappeared as if by the touch of a magician. For their own safety they were indebted to Providence and solid brick walls.

There was a high canal lock at Mauch Chunk. It was a veteran and stood the shock of the freshet of 1841 without trembling. When the rush came last week its good reputation made the quiet water below it a harbor for scores of boats, the crews looking over the river, as well as the darkness would permit, at their less fortunate companions, and blessing their luck. Many of them went to bed. The lock gave way. The boats were engulfed in the torrent, and of the sleepers it is believed that at least fifty awoke to find themselves struggling with a giant whose touch annihilated the great world before the days of Noah. The names of these victims will never be known. They were of course, strangers at Mauch Chunk, earning their living by traveling with the boats from place to place. A number of women were among the lost.

The writer here introduces a good deal of detail showing the immensity of the destruction by the flood, and closes as follows:

It is almost impossible to imagine the devastation caused by the freshet. Every town in the Valley situated near the river was more or less injured.--No details as to the financial extent of the loss can be given. Private citizens awoke to find their cattle and out-buildings washed away. Turnpike and Bridge companies gave up all thoughts of dividends for at least a year, and general devastation conquered the smiling country.

Of three houses which formerly stood near the river, at Allentown, not a vestige remains except an old stove. The cellars are receptacles for sawlogs and miscellaneous lumber. Bedsteads from Mauch Chunk lie quietly side by side, with railroad bridges from White Haven. Carriages in a disorderly condition sport their three remaining wheels in half-broken tree tops, and cellar doors recline gracefully on old canal boats, whose cargoes of coal are leaking out at either end. The story of a miner from Mauch Chunk was a sorrowful one. The man had lost a wife and three children. He came home at a late hour and found a small Niagara rushing past the spot where he had erected his family altar. When the water subsided, he started down the valley to learn the fate of his wife and children. We saw him as he passed Allentown. If he was rough in external appearance, there was no reason to believe but that the heart beneath the vest felt the loss keenly. The bodies will probably never be found. They may sweep into the Delaware, and from thence into the ocean.

'Chain Bridge' or 'Change Bridge', also known as the 'Lehigh Canal Swinging Bridge' and as 'Wire Towing Path at Pool No. 8', is an historic change bridge spanning the Lehigh River at Palmer Township and Williams Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. It was built in 1856-1857, and consists of three stone piers and two spans.

The Chain Bridge was built by the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company in 1857 to enable people and mules to cross the Lehigh River. The bridge was used to ferry the mules across the river, and allowed the animals to tow the boats and barges from one bank to the other. Although listed in the National Register as Chain Bridge, is is actually a change bridge--a special structure with an underpass that allowed mules towing canal boats to move, cloverleaf style, from one side of the canal to the other without unhitching. The bridge is composed of three stone piers and two spans. Each pier is approximately 30 feet high and the center pier is about 40 feet across at water level. At each of the end piers is a metal capping and cable anchorage for the three-inch cables which supported the bridge surface. When built, the bridge was one of the early uses of stranded cable for bridge construction.

The stranded cable was made on the site, possibly by the Roebling Company, who built several suspension bridges, including the Brooklyn Bridge. The bridge was intended to carry only pedestrians and animals, not vehicular traffic. In the 1950s the road surface was removed from the piers. The bridge remains significant because it was an integral part of the long defunct canal system. It is also a fine example of the early use of standard cable for bridge construction. The bridge represents a unique civil engineering solution to a canal era problem and played a vital role in the transportation system that opened up the Lehigh Valley to outside development and established coal as an invaluable heating and industrial fuel.

National Park Service nps.gov

No comments:

Post a Comment