Newark is nine miles west of the Eastside Manhattan docks where immigrant ships docked and one of the first destinations of the Irish who moved on from NYC. Among the Irish people who settled there in the 1820's were several Louth (and also Kilkenny, the county from which James's wife hailed) names whose connections through marriage and baptisms help us understand the families. James Hoy and his wife Margaret Phelan appear in these records in early 1834.

As the town grew so, slowly, did the Irish presence. The eighteenth-century migration to New Jersey was largely of Ulster Presbyterians who brought their earnest egalitarianism to a still fairly sleepy place. Stout and serious people, at times a little uncouth, occasionally irksome, most were firm patriots by the time of the revolution. Quite a few fought in Washington’s army (alongside, it should be said, Irish Catholics, too). Others supported the revolutionary cause both morally and financially. After the revolution, they came into their own. As Newark developed in the early national period — Springfield, Caldwell, Orange Township and Bloomfield all formed separate municipalities between1793 and 1813 — so Irishmen spread into the leafy farmland that would eventually become the New Jersey suburbs. There is hardly a town in Essex or Morris counties that does not have a connection with them through some institution or another — a reformed church, a library, an old mill, an estate, a name.

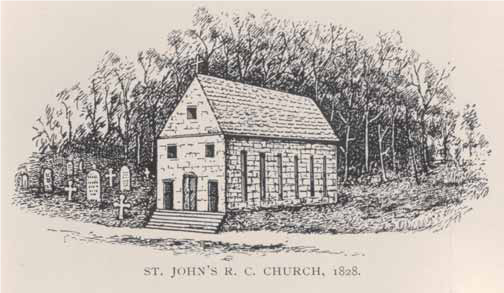

It was not until the middle years of the nineteenth century, though, that this relatively unhurried way of life was broken. Life in Ireland became difficult, then intolerable, in the 1830s and 1840sas economic distress and political disappointment broke the spirit of many Irishmen. Chronic poverty, failed harvests, occasional famine, spelt doom for a rural peasantry that for years had clutched to the land in hope of better times. Those better times never came. Bitterly, men and women made their way to America, so that a trickle at the beginning of the nineteenth century became a stream by the 1820s and a flood by the terrible 1840s when the potato famine was at its worst. There were enough new immigrants in 1826 to warrant the founding of the first Catholic parish in the city — St. John’s in Mulberry Street. The names of the first trustees tell the story: Patrick Murphy, John Sherlock, Christopher Rourke, Maurice Fitzgerald, John Gillespie, and Patrick Mape. The land for the church was bought in 1827, the building finished the following year, a brief succession of pastors appointed until, in 1833, an Irishman, Father Patrick Moran, came to take charge of the parish. For 33 years, Moran’s energy was inexhaustible. Devoting himself to all sorts of social improvements — temperance campaigns, public libraries, schools — he was a model religious and social leader. In 1834 he chose Bernard Kearney, another Irishman, as principal of his first parochial school. Kearney, who had come to Newark in 1828, served for 29 years, becoming as legendary a pedagogue as Moran was a priest. (He was the first to teach stenography in the city, was a stout supporter of the Union cause, and, in 1862, went on to serve in the state legislature.) Newark Catholicism, and Newark itself, owed much to men of this stamp.

St John’s was the first Catholic Church in New jersey. It was founded in 1826. James Hoy and Margaret Phelan were married there in 1834 and their first two children Margaret and Sarah Jane were baptized there.

Yet for all the civic dutifulness of a Moran or a Kearney, the priest and his teacher and their flock represented a different and largely unwelcome kind of Irish presence. These people were poor and Catholic and, somehow, strange. Something about them — their accents, their language, their customs, their attachment to folklore, their religion, their occasional drinking — made them seem un-American. These were not the Irish of Old Newark, reliably patriotic and solid. The truth was that Newark itself was different and this great mass of Mass-goers was only one symptom of the change. As industrialization took hold, with factories and workshops demanding more and more people to make and buy more and more goods, new populations were sucked into the city. Irish and German mainly, the former especially, these first time Newarkers made the streets teem with new and competing ways of life. Newark’s population grew from 6,507 in 1820 to 71,941 in 1860. Moran’s crowd was here to stay. They had come, as the old joke put it, hoping to find streets paved with gold. Not only were there no streets: they were expected to pave them.

It takes only a little imagination to recreate their world. John Cunningham, doyen of Newark historians, has chronicled some of their doings. “The Irish and other ‘lower classes’,” he reminds us, “were particularly suspect when Asiatic cholera struck the city in 1832.” Newspaper accounts of that calamity listed the dead as “Irish” or “colored” or some a simple asterisk for “foreigner.” Even in death, the great equalizer, some were more equal than others. In life, the Irish also found it hard. In the great panic of 1837 — one of the worst banking crises in the history of the country — they were “the last hired and the first fired.” Some left the city altogether, heading west beyond the Allegheny Mountains in hope of better times — that old Irish and, now, new American hope. The rest stayed, waiting for luck to turn. For some it was a long wait. But there was work. As well as providing muscle for building railroads and canals, the Irish worked in Newark’s stone quarries, as coachmakers, as hatters, as oddjob men, as painters, as cobblers — as anything. They were not in a position to be choosy.

Helping to shape these newcomers into moral decency was the church. After the founding of St. John’s Parish, there were enough Irish Catholics to justify the building of another church — St. Patrick’s on Washington Street — built on land bought by Moran in 1846 and dedicated on March 10, 1850. It remains one of the loveliest churches in the city. Three years later, the Diocese of Newark was established, its territory the whole of the state. The first bishop was James Roosevelt Bayley, “popish” convert from an old Episcopalian family. St. Patrick’s served for many years as his and his successors’ cathedral. Bayley’s appointment marked a coming of age, also, less appealingly, a growing hostility to the alien presence of his people and their creed. His installation as bishop was marred by ugly scenes — heckling, jeers — a mixture of anti-Irishness and anti- Catholicism typical of the “Know-Nothing” movement of the 1840s and 1850s. This “nativism” turned nastier in September 1854 when St. Mary’s (German) Church in Newark was attacked by some local and mainly imported members of the anti-immigration American Party. An Irishman died in the violence, another mortally wounded. One sign the Irish were here to stay was that so many other people wanted them to go.

But they had no intention of going.

(From The Irish in Newark and New Jersey By Dermot Quinn, professor of Irish and British History at Seton Hall University)

No comments:

Post a Comment