Source: Archaeology Ireland, Heritage Guide No. 21: Ireland in the Iron Age: Map of Irelandby Claudius Ptolemaeus c. AD 150 (March 2003)

Published by: Wordwell Ltd.

Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus), working in the renowned library of Alexandria in Egypt, completed most of his major works in the middle of the second century AD. Apart from his geography, his works included treatises on astronomy, mathematics, astrology, music and philosophy. In its time his work was the most accurateand most comprehensive of geographical texts and was used throughout the medieval period as the foundation for other maps of Europe.

Ptolemy's geography is considered to rely heavily on the work of a fellow geographer, Marinus of Tyre, whose works do not survive. Little is known of Marinus, but it is thought that he preceded Ptolemy by a short time and that he had based his geography on the works of previous scholars. This raises the likelihood that Ptolemy's information is a mixture of both historical and contemporary sources. There is no doubt that the knowledge of river-mouths in particular indicates that mariners were the original sources for the outline map of Ireland. But the names of tribes and places in the interior of the island indicate that traders or merchants may also have provided information.

Ptolemy's map of Ireland, which is only a portion of his overall map of Europe, ranks among the most important yet most enigmatic documents referring to early Ireland. The information recorded is of immense interest to archaeologists, historians,linguists and classics scholars. The primary importance of the map is that it is a depiction of Ireland at a time when there are no other contemporary descriptions and when other references to the island are both scarce and brief.

By modern standards the schematic map derived from Ptolemy's coordinates is reasonably accurate in its overall depiction of Ireland, a testament to the detailed observations and mathematics of early scholars. It is not known whether Ptolemy's text was illustrated with a drawn map, for none survives. However, it is likely that he used some form of graphic representation in order to calculate the coordinates that he includes in the text.

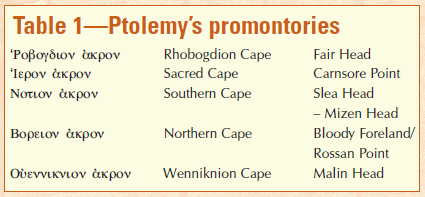

In his text Ptolemy records the positions of fifteen river-mouths,five promontories, eleven towns and nine islands. Furthermore, he indicates the relative positions of sixteen tribes and gives names to four surrounding oceans. The general characteristics of the east coast of Ireland are more easily recognised than those of the west coast, which is less well represented.

The names are one of the most interesting features of the map.

Some are of a geographic or positional nature and are unlikely to have been authentic indigenous names; they may have been names used by the mariners and traders who were the sources of Ptolemy's information. Others are likely to be authentic placenames, although no modern or even historical equivalents are easily recognisable. Yet others are Greek renditions of what are clearly Celtic names, and some of them are recognisable in their modern form. Names below are represented in Romanised form from the Greek.

The older Greek version of the name for Ireland was Ierne (Ιερνη)but Ptolemy calls the island Iwernia (Ιονερνια), one of the Prettanic Isles (Πρεττανικαι νησοι), the 'islands of the Picts'. The name of Ireland may have been a corruption of the insula sacra rendered in Greek as 'ιερα νησος, 'sacred island'. Almost 200 years before Ptolemy Julius Caesar had referred to Ireland as Hibernia,which became the common Latin name for the island. The word Hibernia is also related to the Latin adjective hiberna, wintry orcold, usually explained by scholars as indicating a perception of Ireland as a cold, wintry place.

Ptolemy names four 'oceans' around Ireland. On the north is the Hyperboreian, which is the sea 'beyond the north'. It is likely that this is a purely geographical term used by seafarers. Likewise the'Western Ocean' refers to the Atlantic and marks the westernmost sea recorded in Ptolemy's geography. Wergionios is the name applied to the sea at the south of the island, while Iwernikos occupies the east coast of the island and is named after the Iwerni, the tribe named on the south of the map.

Viewed from the sea, promontories are the most notable landscape features, and four of these mark the extent of Ireland. Ptolemy's word for promontory or cape is akron.

Of the five promontories listed two have positional names-the northern (Boreion akron) and southern (Notion akron) promontories-and again these may have been descriptive names applied by Ptolemy himself or used by seafarers who had a concept of the layout of the island. The exact location of the Northern cape is unclear, but it could be Rossan Point or, more likely, Bloody Foreland, Co. Donegal. Positionally, the cape of Wenniknion corresponds to the location of Malin Head, sharing its name with the nearby tribe, the Wenniknioi. The nearby Widua would then correspond to Lough Foyle. On the north-east the cape of Rhogbogdion corresponds to Fair Head and likewise shares its name with the tribe referred to as Rhogbogdioi.

Ptolemy's 'Southern Cape' is more difficult to identify owing tothe lack of information on the west coast, but it could equate with any of the numerous promontories between Slea Head and MizenHead. The 'Sacred Cape' corresponds to Carnsore Point, which marks the south-eastern corner of Ireland. This name may be linked to the name applied to Ireland.

The promontories are crucial to Ptolemy's map in that they define the shape and extent of the island of Ireland. It is interesting to speculate that the positions of the four capes may have been deliberately determined by some mariner or geographer in order to give some control points for the map.

Ptolemy's nine islands are the least accurate features of his map of Ireland. He records two groups-six named islands to the north-east and three islands on the east coast. Given that his projection of Scotland is inaccurate, it is likely that many of the northern islandsare similarly incorrect. Indeed, some of these islands should be associated with the west coast of Scotland.

On the west of the northern group two of the islands are named Aibuda. This is similar to the collective name used by Ptolemy for the Hebrides. Malaios may refer to the Isle of Mull, while Epidionmay correspond to the Mull of Kintyre. The name Rhikina may be the Greek rendition of Ricina, the early Celtic form of the name for Rathlin. Monaidos is the southernmost island of the northern group and is considered to represent the Isle of Man, although it is totally out of position.

Two islands, Adrou and Limnu, are located midway along the east coast in the Irish Sea. Both are described as 'desolate' or'deserted'. O'Rahilly considered that Adrou may be connected with Bean Edair, the Irish name for Howth. Limnu, then, cannot be Lambay as it lies to the south of Adrou, according to Ptolemy.

For 'town' Ptolemy uses the Greek word πολις, polis. However, most scholars agree that in the absence of archaeological evidence for towns in prehistoric Ireland polis is likely to indicate centres or concentrations of settlement. Ptolemy designates Isamnion as a promontory, but Muller and Orpen agree that Isamnion is to be understood as a town. O'Rahilly states that the word is likely to contain an element of Emain, the capital of Ulaid. The town Eblana and its tribe the Eblanioi are located south of the Boyne, most likely in the area now referred to as Fingal. O'Rahilly states that Dounon 'is agood Celtic word'. It is found in Ptolemy as a placename element for towns or hillforts in Britain and Gaul, although Ptolemy's dún has no qualifying word to distinguish it from any other dún. Orpen speculated that it may be connected with Rathgal in south-west Wicklow, the general area where Ptolemy located it. O'Rahilly favoured the proposition that Dounon may have referred to Dind Ríg, the seat of the ancient kings of Leinster, near Leigh linbridge in County Carlow.

Alternatively, the name may refer to Dún Ailinne, the 'royal capital' ofthe early kingdom of Leinster.

Manapia is located close to the mouth of Ptolemy's Modonnos river in the territory of the Manapioi. The name of the tribe is thought to be avariant of the Gaulish tribe known as the Menapii. The letter p in this name gives rise to speculation regarding P-Celtic traces in this part of Ireland and the possibility that the Manapioi may have been recent migrants from Gaul. Freeman states that it is equally possible that P Celtic speakers may have relayed the name with p rather than q.

Iwernis is located north-west of the River Lee but no equivalent placename survives.

Two towns are named Rhegia, one in the northern half of the country and the other in the south. The name may be connected with the Celtic root word *rigia, indicating royal seats. O'Rahilly speculates that the location of Rhaiba suggests a connection with Loch Ríb (Lough Ree).The inland towns of Laberos and Makolikon have no obvious equivalents in terms of their name or location. Nagnata is a town associated with the tribe of the same name somewhere in the region of Mayo. Orpen preferred the reading Magnata for this name, likening it to 'Moyne' and even Magh-eo,from which Mayo derives its name.

Sixteen tribes are mentioned in Ptolemy's text. Unlike the other elements of the map, his tribes are not given a 'precise' location but are merely indicated by their position in relation to one another around the coastline. Some tribes can be assumed to occupy the towns or promontories which share the same name.

On the east the Rhogbogdioi occupy the area around the cape of Rhogbogion and may be related to the Dál Riata of early history who founded a kingdom in Argyll in Scotland in the fifth century. To the south of them are the Darinoi, whose name may be connected with the name Dáire, presumably an ancestor deity. It is interesting to note that Dundrum in County Down in the territory of the Dál Fiatach is known as Dun Droma Dáirine.

Woluntioi is one of the more recognisable tribal names on the map. It is undoubtedly connected with the Ulaid, occupying an area between Isamnion, possibly Emain Macha, and the Buvinda on Ptolemy's map. In the early historic period they were known as the Dál Fiatach and occupied the area between Dundrum Bay and Belfast Lough. Their historic centre was at Dún-Dá-Lethglass (Downpatrick), originally a secular rather than a religious site.

The town of Eblana is the focus for the Eblanioi, a name which does not have any easily determined historic or modern equivalent. Kaukoi, as is often remarked, is reminiscent of the Cauci known from Germany, but there is not thought to be any direct connection. O'Rahilly suggests that historic Cualann may be implied, given the location in the Wicklow area.

These are followed by the Manapioi, occupying the area around the coastal town of Manapia. This is the same name as Menapii, a Gaulish tribe found on the banks of the Meuse and lower Rhine, known in the early historic period as the Manaig. The Manaig genealogies are tied in with the Uí Bairrche of south Leinster, whose origins may go back to the Brigantes. Given that the Manapii and Brigantes are neighbours on Ptolemy's map, it is not surprising that there is such a connection in the later sources. Forgall Manach, father of Cú Chulainn's wife Eimear, had his bruiden (Otherworld residence) at Lusk, Co. Dublin, near which is the promontory fort known as Drum Manach.

To the south of the Manapioi are the Coriondoi, somewhere in the south Wicklow/north Wexford region. While the name is totally unknown in any Irish records, O'Rahilly observed its similarity to Coriono-tatae, 'the name of a people in Britain known in an inscription at Hexham (in the territory of the Brigantes)'. The Brigantioi, a tribe presumably connected to the Brigantes of northern England, can be placed in the area of south Wexford. Freeman notes that there may be no connection as it is equally possible that places and tribes throughout the Celtic world could bear similar names. F. J. Byrne suggests that the Irish Brigantes may be associated with the mythological Brigit. The Munster Déissi had a tribe known as the Uí Brigte, descendants of Brigit, and in historic times Saint Brigit is portrayed as defending Leinster (Laigin), terrifying enemies in the same way as the goddesses Macha, Badb and the Morrigu in heroic sagas.

The Iwernoi occupy the territory around Iwernis, north of the Dabronis, somewhere in the vicinity of Cork. The name may be related to the Érainn, who appear in later sources as one of the ancient population groups from whom many of the tribes of the early historic period claimed descent. The next tribal group are the Wellaboroi, sited near Ptolemy's Southern Cape. The name could also be reflected in the twelfth-century Book of Leinster poem 'The battle of Luachair, hero-home of Fellubair' (Cath Luachra laechdu Fellubair).

The Usdiae tribe are possibly to be equated with the later Osraige (Ossory) of Leinster, who were originally a Munster tribe. The Ganganoi, located somewhere in the north Kerry/Limerick area, are also in north Wales according to Ptolemy. The Auteinoi may have an association with the Uaithni of the Lough Derg area on the Limerick–Tipperary border. The baronies of Owneybeg and Owney in Limerick and Tipperary preserve the name.

The name Nagnatae, located in the Mayo region, may conceal an old name for Connacht. According to tradition, the Fifth beyond the Shannon was once known as Cóicéd Ól nÉcmacht, 'the fifth of the Fir Ól nÉcmacht' (or Néchmacht). Two tribes, the Erdinoi around the Erne and the Wenniknioi near Malin Head, occupy the north-east of the country. Mac an Bhaird links the Wenniknioi with Dunfanaghy (Dún Fionnchaí) on etymological grounds.

After the promontories, Ptolemy's rivers are the features next most likely to be accurate. Ptolemy does not indicate the course of any of the rivers but merely records their ekbolai. For early mariners such river-mouths would have been essential in terms of shelter from storms; presumably they were also the location of trading points around the Irish coast and thus would have been well known.

Some bear names that have a recognisable modern equivalent, while others have equivalents in early Irish forms. The position of some leaves no doubt as to which river Ptolemy intended, while others have both a name and position which are considerably more enigmatic. Table 2 lists the rivers and their equivalent modern names. Of the fifteen rivers, those along the east coast have the most accurate positions. The Lagan is almost certainly the river named Logia by Ptolemy. O'Rahilly favours this identification on the basis that Belfast Lough was known as 'Loch Loíg', loíg being the Irish word for 'calf'. The Winderios is more difficult to identify but, as Freeman notes, it could be Carlingford Bay or Dundrum Bay on the County Down coast. Alan Mac an Bhaird suggests that it may be Strangford Lough, as Ptolemy's name may be preserved in the name 'Finnabrogue' found at the mouth of the lough.

It is curious that the River Boyne, that most archaeological of rivers, is clearly named Buvinda by Ptolemy, clearly the Greek rendition of Bo finne, the 'White Cow' goddess after whom the river is named. The next river south of the Boyne is Ptolemy's Oboka and here more confusion arises. It should, of course, refer to the Liffey, the next most prominent river estuary. However, the fact that there is no correspondence in the name has led some to consider that Ptolemy has either omitted the Liffey or has made an error in the name. O'Rahilly considers that the Modonnos is the river which we now call the Avoca, the name deriving from Ptolemy's Oboka.

On the south coast the Bergios is considered to be the River Barrow and thus refers to the Waterford Estuary. O'Rahilly notes that the Dabrona must be the River Lee where it enters Cork Harbour, based on its position and the fact that the old name for the Lee was Sabrann, implying that Ptolemy has been misread and that his river should be the Sabrona.

The Iernos is located on the west coast, north of the Southern Cape, and its name may be associated with the tribe and city of the Iwernoi recorded by Ptolemy. Freeman considers that it may be the mouth of the Kenmare River and that Dur may be Dingle Bay. Senos, based on the similarity of the name, is almost certainly the Shannon, although Orpen suggested that it may refer to the Kenmare River on the basis that the Kenmare was called inbher Scéne in bardic literature.

Neither the Ausoba nor the Libnios can be identified with any degree of exactitude, but Freeman suggests Galway Bay and Clew Bay respectively. The Ravios fits well with Donegal Bay and thus may refer to the River Erne. O'Rahilly equates the name with that of the River Roe in County Derry and considers that Ptolemy's names 'may have become disarranged at this point'.

On the north coast the Vidva is likely to refer to Lough Foyle, while the Argita, derived from *argento-, meaning 'silver', would fit well with the position of the River Bann.